Polarized, black-and-white thinking is a big problem. It distorts our understanding of realities involving shades of gray, which most human realities are. Binary thinking produces misleading maps of a complicated, nuanced world.

When we face difficult situations, all-or-none thinking blinds us to the possibility of a middle ground, leaving us with only simple, extreme options that rarely work. This type of cognition results in maladaptive emotions and behaviors, an array of mental health diagnoses too numerous to mention, and in its milder and more common forms, all sorts of problems in living and relationships.

Everyone engages in black and white thinking sometimes, because it is quicker and easier than careful consideration of a spectrum of possibilities. Problems arise when we rely on it too much, especially in dealing with emotionally important situations, issues and relationships.

Persistent problems in a particular life area suggest that some kind of dichotomous thinking is going on below the surface, driving the ineffective functioning. This is especially true when extreme emotions and/or behaviors occur, because these are the hallmarks of polarized cognition.

The Value of Balance

When styles of psychological functioning are conceptualized on a continuum, effective styles are usually located in the mid-range—the Goldilocks Zone. For example, in responding to conflicts, passive behavior is usually ineffective, and so is its opposite, aggression, while the option in the middle, assertive behavior, is most likely to be effective. Lots of things work this way, as described by great psychologists from Aristotle to Marsha Linehan (2014) and summarized in the first post of this blog and my book, Finding Goldilocks (2020).

Of course, this paradigm doesn’t apply to everything—it applies to personality-related styles or ways of operating, as opposed to traits that are good by definition, like skills, talents, and capabilities. For example, the type of spectrum we are interested in would not have “socially skilled” at one end and “socially awkward” at the other, but it might have “aloof” at one pole and “clingy” at the other, because these words describe opposite styles of interpersonal functioning, with “friendly” in the middle.

Constructing an Individualized Scale

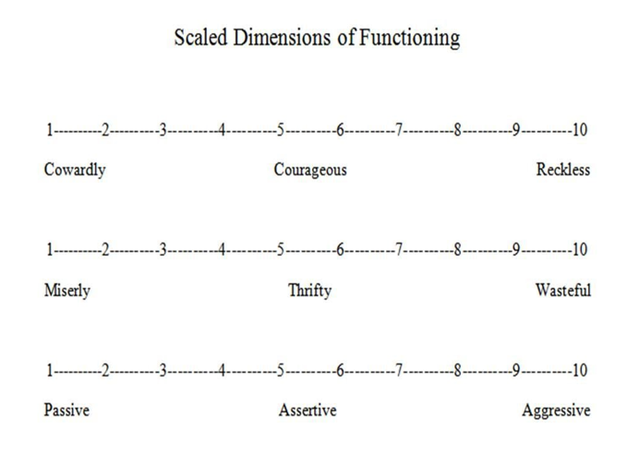

If you would like to use this paradigm to conceptualize a psychological problem and point the way toward change, the first step is to identify the relevant spectrum: the dimension of functioning on which the ineffective style is located. Ten-point scales are handy tools for this task because they provide a spatial analogy and numbers to supplement our usual reliance on words. Here are some classic examples:

This scaling exercise works best if it is done in writing, so you can see what you are doing and use spatial information as well as words. To define the spectrum relevant to a problem important to you or someone you know, draw a 10-point scale on a piece of paper or in a computer file. Then, briefly describe an extreme version of this style of functioning under scale-points 8 to 10. One word might be enough to define this pole of the spectrum.

Next, briefly describe the opposite style of functioning. Do not just describe the absence of the style (e.g., not reckless, not wasteful, not aggressive)—define the reverse of that way of operating (e.g., cowardly, miserly, submissive). If you are constructing a scale for a personal issue, think about the way of functioning you most dislike, fear, or want to avoid. To find the right words for scale-points 1 to 3, think of ways of functioning that are extreme on this dimension. These will generally correspond to psychological styles that are dysfunctional but in a way opposite to the style which has been the problem.

Next, with the continuum defined by its poles, write words or phrases that describe the moderate middle under scale-points 4 to 7. (5.5 is the exact midpoint.) This style should represent a synthesis or balance that combines positive elements from the two extremes on either end of the spectrum. It might also be useful to describe the two intermediate regions between the midpoint and poles. Whether you include this or not, you have completed a first draft of your scale.

Now it is time to indicate where you (or the person you’re doing this for) are located on the spectrum. You can give your answer in the form of a number or mark on the scale. If it’s hard to decide between two numbers, use a fraction or decimal. This number probably summarizes a lot of information in a very succinct way. You have done a preliminary assessment on a spectrum—but let’s delve further into this method of analysis so you can circle back and, if appropriate, revise your scale and do a more definitive assessment.

Cognition Essential ReadsHere is an example based on the spectrum of possible responses to direction from others. Oppositional people usually value their independence a great deal, and they hate the idea of being controlled by others or obeying authority in an unquestioning manner. These individuals sometimes misunderstand their need for autonomy to mean they must constantly push back against direction from others in order to preserve and protect their independence. This problem is based on black-and-white thinking: The person feels she must choose between being controlled by others and constantly opposing them. The problem could be solved if the person had a more accurate picture of the range of possibilities in between. Here is the relevant spectrum:

Many psychological issues work this way: Opposite styles of functioning have advantages and disadvantages, both are maladaptive in their extreme forms and, when balanced in a moderate synthesis, the result is a flexible, effective style. On 10-point scales, such styles are located in the middle of the spectrum, in the 4-7 range.

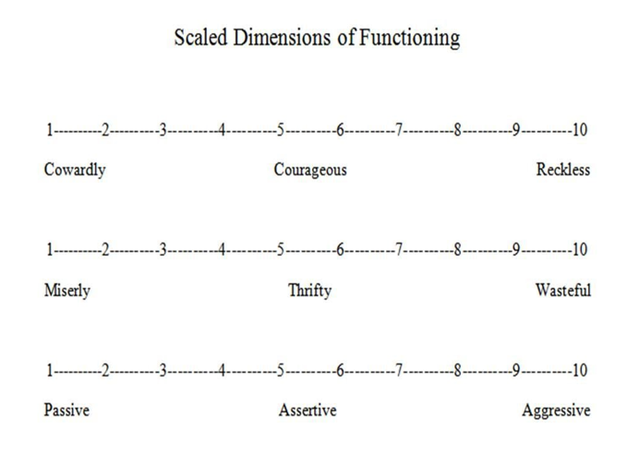

Here are three more diagrams of three more problems that have come up in my work with clients. I provide no explanations because, if the diagrams were composed well, you will be able to identify the dimension of functioning that was problematic for the client—although you won’t be able to tell at which extreme he was located when therapy began, because that does not matter to the spectrum.