We all know that weather and visibility are huge factors in determining if a flight is possible on any given day. Complex terms like VFR and IFR represent flight rules that govern these weather minimums. They can make or break your chances of taking off.

In this guide, we’ll cover the meaning of VFR and IFR, how they differ, and why all pilots must understand these rules intimately before heading skyward.

What VFR stands for Visual Flight Rules. This refers to flying an aircraft while maintaining visibility and separation from obstacles and other traffic using visual reference outside the cockpit.

Under VFR, pilots fly when weather conditions are favorable, allowing them to navigate by sight rather than relying solely on instruments. They are responsible for “seeing and avoiding” other aircraft and obstructions.

It’s also a skill set that requires pilots to be keenly aware of their surroundings and make decisions based on what they see outside the cockpit.

This type of flying is most common on clear, sunny days when visibility is high, and it’s perfect for pilots who enjoy the hands-on experience of flying by sight. It’s the go-to method for student pilots, private pilots, and those flying smaller aircraft, offering a blend of freedom and responsibility.

Simply put, it is Instrument Flight Rules (IFR), referring to how pilots should fly by reference to instruments rather than outside visual cues. It includes the set of rules and procedures pilots follow when the weather isn’t clear enough to navigate by sight.

Under IFR, pilots use aviation instruments like attitude indicators, heading indicators, altimeters, and airspeed indicators to control the aircraft. Precise IFR navigation relies on equipment like VOR receivers, GPS, and glide slopes.

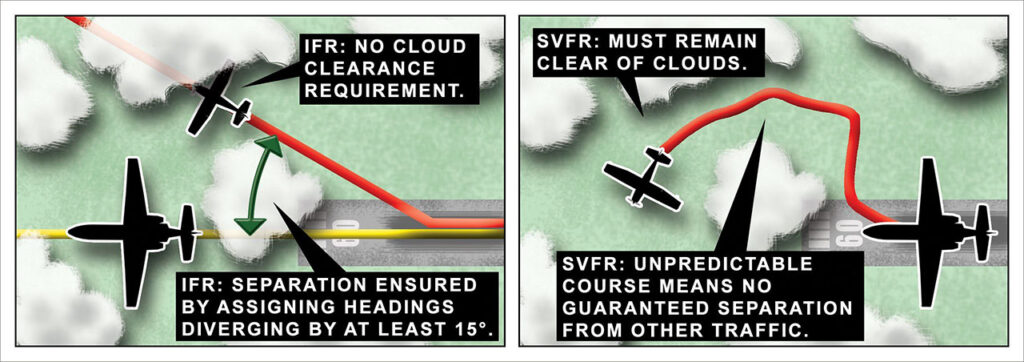

Since clouds and low visibility prevent visual flight, pilots rely entirely on these instruments to fly predetermined routes while maintaining separation from terrain and other aircraft. Air traffic control may also provide clearances and guidance at the same time.

This type of flight provides added flexibility but is more complex than VFR. It requires extensive flight training and specific instrument ratings. Aircraft must have specific instrumentation and radios to fly in instrument meteorological conditions.

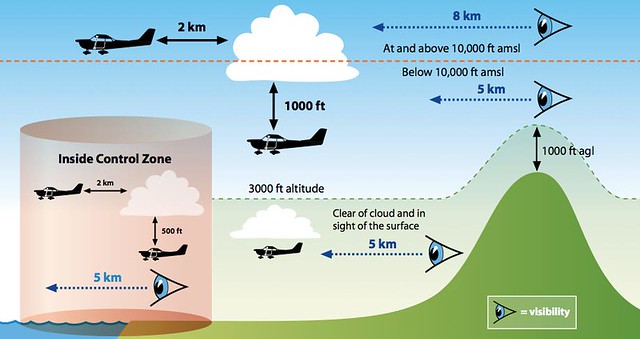

VFR is more straightforward and works best on those perfect, cloudless days. It requires minimum visibility and cloud clearance to operate by visual reference outside the cockpit. Pilots must be able to see terrain, obstacles, and other traffic.

However, when the weather decides not to cooperate, with clouds rolling in or visibility dropping, VFR no longer cuts it. VFR flights must be canceled if weather conditions deteriorate below those minimums, including at night.

That’s where IFR steps in, designed for the days when looking out the window offers little to no guidance. It enables pilots to fly in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) with low visibility and cloud cover.

Regulators like the FAA use categorical outlooks to classify weather conditions to guide aviators, including airline pilots, in making these decisions. These categories (LIFR, IFR, MVFR, and VFR) offer a quick snapshot of expected flying conditions, each defined by specific visibility and cloud ceiling criteria.

VFR conditions, shown in green, represent the ideal for pilots who prefer visual navigation. With visibility over 5 miles and a ceiling above 3,000 feet, pilots can navigate using the terrain and other visual landmarks.

With visibility between 3 to 5 miles and/or a cloud ceiling of 1,000 to 3,000 feet, MVFR conditions are depicted in blue.

While pilots can still operate under visual rules, the margin for flight safety is thinner. Pilots must be prepared for changing conditions and might need to rely on instruments more than in clear conditions.

IFR conditions occur when visibility is between 1 and 3 miles and/or the ceiling is 500 to 1,000 feet. Marked in red, IFR requires pilots to navigate primarily using instruments rather than visual cues.

When visibility drops below 1 mile and/or the ceiling is less than 500 feet, conditions are classified as LIFR. It’s marked by a magenta color on charts.

LIFR conditions suggest extremely limited visibility and require pilots to rely heavily on their instruments. Flying in LIFR conditions is challenging and demands significant skill and concentration, as well as the appropriate aircraft certifications.

Learning to fly VFR is often the starting point for pilots in their flight schools. It focuses on basic aircraft handling and navigation using visual references and situational awareness. This includes understanding the landscape, spotting landmarks, and maintaining spatial awareness in good weather conditions.

Transitioning to IFR is another story, especially in instrument training. This is where the training dives into complex procedures and equipment readings, and pilots sometimes need to learn to trust what the aircraft instruments are saying over what they see.

IRF training is a more rigorous process and demands a more significant investment in time and education. But in the end, it equips pilots with the skills required to navigate through bad weather conditions and ensure safety when the skies aren’t clear.

The FAA recommends filing a flight plan, but it is not always mandatory in controlled airspaces for VFR flights. They may need, at most, to establish two-way radio communication or get clearance from the air traffic controller (ATC).

However, flight plans are a must for IFR. This detailed document outlines your route, expected times, altitudes, and other critical information. This plan becomes ATC’s guide to tracking and assisting you through controlled airspace.

The reporting requirements ramp up under IFR, too. Pilots need to check in regularly with ATC and update them on their position, any deviations from the plan, and their next steps. It’s a continuous loop of communication that keeps everything running smoothly.

The ability to operate in all airspace classes is a major advantage of IFR flight. Once they get their flight plan rubber-stamped by ATC, they’re good to go pretty much anywhere, even in busy airspace. This allows more direct routings and flexibility in many situations, such as cross-country flights.

Meanwhile, the FFA doesn’t allow VFR operations in Class A airspace. They can only fly in Classes B through E and uncontrolled airspace (Class G).

For VFR, the equipment list is pretty basic, with only fundamental navigational and communication tools. This includes navigation radios, transponders, lighting, and basic flight instruments for attitude, altitude, and airspeed. A GPS is recommended but not required.

IFR, however, is a different ball game with different rules. Pilots need a suite of advanced equipment designed for precision, navigation, and communication.

First off, you have to get the right navigation system. VOR (Very High-Frequency Omnidirectional Range), ILS (Instrument Landing System), and GPS for the modern aviator are some common examples.

Then there’s the transponder with Mode C, which lets everyone know exactly where and how high you’re flying.

The advanced avionics come from the precise nature of IFR flight. While not cheap, they transform an aircraft into an all-weather machine and provide added safety. That is why VFR remains the more accessible option for many.

This decision often boils down to a mix of weather conditions, pilot qualifications, and what you hope to achieve with your flight.

For many enthusiasts, VFR is their go-to when the skies are clear. They can navigate by looking out the window, enjoying the views, and manually controlling their flight path. It’s perfect for local flights, training exercises, or just enjoying the freedom of flying with fewer restrictions.

IFR takes the crown when weather conditions are less than ideal. It’s also a must for flights in certain controlled airspace, where a precise flight path is important for ATC people.

Pilots lean towards IFR for its precision and reliability, especially in less-than-perfect conditions. IFR makes it possible to fly routes that might be off-limits under VFR, such as at night, by relying on instruments.

Yes. But you need to contact air traffic controllers to make the change official. In certain circumstances, you can even get a clearance without a flight path (pop-up clearance).

Yes, though it isn’t a common practice, and we certainly don’t recommend it. The FAA, in particular, has no special requirements for those making a flight at night under VFR. However, regulators in other countries may have some restrictions on this operation.

IFR and VFR aren’t just regulatory hurdles. They also help enhance your command in the cockpit and your freedom in the skies. A deep dive into either flight mode is necessary for any pilot’s training. We hope this guide has shed light on these pivotal flight modes for your education or enjoyment of flying.